Why WiFi Money is the Best Way to Survive Hyperinflation

History is telling you how to survive: are you listening?

At the start of World War I in 1914, the exchange rate of the German Papiermark was 4.2 marks per dollar. The value of the mark dropped throughout the war, falling to 48 marks per dollar by the time the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919.

By 1923, the exchange rate was 4,210,500,000,000 marks per dollar.

Almost 100 years after the most famous episode of hyperinflation in history, we’re on the cusp of another monetary apocalypse that is going to change life in America (and everywhere else) as we know it.

The inflation might be inevitable but your suffering is not. In this article, I’m going to explain why owning an online business - aka WiFi money - is the best path to survival in a hyperinflationary environment.

How it happened

Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic began the same way hyperinflation always begins: monetary expansion due to an “emergency”.

In 1914, the German army swept through Belgium and into France, starting a war that would last over four years and claim the lives of millions of people, leaving millions more wounded and disabled. The overwhelming cost associated with keeping the German army fed, trained, and equipped in the trenches of the Western Front and elsewhere was bleeding the German government dry.

To help pay for the unprecedented cost associated with what was - at that point - the deadliest war in human history, Germany suspended the gold standard. Rather than imposing an income tax, the government decided to finance the war by printing money and borrowing.

This set off a chain of events that would eventually result in a currency devaluation so severe that people buried their dead relatives in cardboard coffins and shoppers carried suitcases full of money to buy groceries. When thieves attacked them they would steal the suitcase and leave the currency behind.

“Partly because of its unfairly discriminatory nature; it brought out the worst in everybody…It caused fear and insecurity among those who had already known too much of both. It fostered xenophobia. It promoted contempt for government and subversion of law and order. It corrupted where corruption had been unknown, and too often where it should have been impossible. It was the worst possible prelude to the Great Depression; and thus to what followed.”

- Adam Fergusson, When Money Dies

In August 1914, that dystopian reality was still far in the future. The world was at war, and Germany needed to find a way to pay for it. Under Karl Hefferich, the State Secretary for Finance, the Reichsbank suspended the convertibility of paper notes for gold. Loan banks were set up, with funds provided via the printing press. These banks gave credit to businesses and municipal governments as well as advanced money for war bond purchases. The loan bank notes became legal tender and entered circulation immediately.

This scheme was designed to pay for the war without raising taxes. It turned the mark into a ticking time bomb the second it was implemented.

The only question was when it would explode and who would be most affected.

Early stages of hyperinflation

The Reichsbank slogan mark gleich mark (a mark is a mark) was meant to reassure the population that the new paper mark was just as valuable as the gold mark that it had replaced. Reality, however, conflicted with the propaganda campaign as the mark began depreciating and prices started rising.

“In a lengthy interview many years afterwards, Erna von Pastau, whose father was a small Hamburg businessman who ran a fish market, made the same point: ‘We used to say “The dollar is going up again”, while in reality the dollar remained stable but our mark was falling. But, you see, we could hardly say our mark was falling since in figures it was constantly going up - and so were the prices - and this was much more visible than the realization that the value of our money was going down… It all seemed just madness, and it made the people mad.”

- Adam Fergusson, When Money Dies

As the prices continued to skyrocket, the German population reacted by demanding more marks rather than policies that would give them more purchasing power. The government obliged them by printing more money, over and over and over again.

The result was that essential items became more scarce while the money in circulation available to buy those items became more abundant.

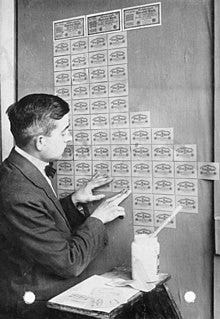

The state attempted to cover up the effects of its disastrous monetary policy by appealing to patriotism, encouraging people to sacrifice for the war effort. “I gave gold for iron” became a popular slogan used by people who sold their jewelry to buy war bonds. These war loans turned private investments into paper claims on the government.

Germany also instituted a censorship regime. The stock market was closed for the duration of the war and foreign exchange rates were not published. This lack of data led many people to believe that the increase in prices was due to the war, not due to bad decisions made by their own government.

By the time Germany lost the war, the standard of living had dropped by half.

“The more materialist the society, the more cruelly it hurts.”

- Adam Fergusson, When Money Dies

The Treaty of Versailles threw fuel on the flames of the inflationary spiral. Germany lost its colonies and one-seventh of its territory along with a tenth of its population. France was allowed to occupy the economically-productive Rhineland region and exploit the coal resources of the Saar. The terms also required Germany to disband the majority of its army, instantly plunging hundreds of thousands of men into unemployment.

All of those terms hurt Germany’s economy; but the real death blow came in the form of reparations, to be paid to the victors of the war both in money and in-kind.

Losing control

After a series of conferences, the first payments were made to the Reparations Commission in June 1921. In August, the exchange rate dropped from 261 marks per British pound to 310. German banks began buying foreign currency at any price.

While the mark continued to depreciate and prices increased, farmers began overcharging or withholding their produce from the market. Workers became unable to afford basic necessities and refused to work without wage increases. Political extremism increased. In August, Mathias Erzberger, the German official in charge of the Armistice Commission (responsible for agreeing to make reparations payments), was assassinated.

“Social unrest was one of the obvious symptoms of inflation.”

- Adam Fergusson, When Money Dies

Once it became clear that Germany would not be able to meet the reparations deadlines, the state responded by increasing taxes on a population that had already seen their standard of living decline precipitously. Regular citizens began hoarding foreign currency, both as a hedge against the declining value of the mark and as a way to prevent taxation.

As the mark declined in value, the stock market continued to reach record highs. In October 1921 the mark hit a new record low of 600 to the pound.

During this period of time, the average citizen wasn’t completely sure if the economy was going to recover or continue to deteriorate. They were angry that their standard of living had decreased and that taxation had increased, but shops were still selling huge quantities of goods. Share prices skyrocketed and stock exchange orders were so abundant that the banks were days behind in opening new letters.

Capital continued to flee the country; primarily to the U.S. dollar, Swiss franc, and Dutch guilder. With no one willing to hold marks and an unbalanced budget caused by wartime reparations, the inevitable happened and the mark began its freefall.

Decline to hyperinflation

The extreme rate of inflation decimated the middle class. The value of the war bonds that they had purchased lost value to the point of being almost worthless. A one million mark investment that was originally worth 45,000 pounds sterling declined to a value of 1,000. A retiree with a pension of 10,000 marks that was originally worth 500 pounds declined to 10. Insurance policies became worth less than the premiums the holders had paid out.

Additionally, professional classes did not have labor unions that could collectively bargain on their behalf. The result was that bankers, professors, and other white collar works suffered the most while blue collar workers were at least able to maintain a reasonable - although greatly reduced - standard of living.

To clamp down on rising costs, the government imposed rent restrictions and subsidies. These subsidies allowed foreigners to buy up German goods at much cheaper rates, which led to movable capital escaping the country. Foreigners didn’t just buy German consumer goods but also bought entire factories and invested in German businesses.

The situation deteriorated to the point that customers began lining up outside of shops before the doors opened, hoping to buy anything that was in stock before the prices increased.

“It is no uncommon spectacle to see queues of intending purchasers lined outside the shops waiting for the doors to reopen. In these circumstances it is evident that retail stocks will soon be sold out and that replacement of them will cause prices to rise very much higher…In almost every camera shop, the sight of a Japanese eagerly buying is a common sight, but on the whole, it is the Germans who are doing most of the retail buying and laying in stores for fear of a further rise in prices or a total depletion of stocks.”

- Paget Thurston, British Consul-General in Cologne

In November 1921, the mark dropped to 1,300 to the pound and food riots started.

The government responded by considering absurd measures such as making gluttony a crime. The Prime Minister of Bavaria proposed a bill that would make it illegal to be "one who habitually devotes himself to the pleasures of the table to the degree that he might arouse discontent in view of the distressful situation of the population”. The proposed bill would fine a first-time offender 100,000 marks and jail them for five years upon a second offense. It also had provision for punishing caterers for “aiding and abetting gluttony”. The bill was not passed, but shows the desperate and preposterous nature of the situation.

Financial speculation was rampant, since assets were inflating alongside consumer goods. Regular citizens spent as much as they could on both.

“As regards dealing in shares, all classes of the population have been speculating with a fine disregard for common sense. Shares have been freely bought in totally unknown concerns, in some cases with the object of trading valueless paper money for what was considered a good security, but generally in the hope of profiting by a rise in the stocks. Shares in respectable concerns which had paid a 20 percent dividend, say, were pushed higher and higher until the holders could not expect a return of even 1 percent…

“ The previous fall in the mark had produced unfortunate results by driving the population in shoals into the shops in a mania of purchasing. While abusing the foreigner for buying out Germany with his profitable rate of exchange, the native has been no whit behind in emptying the shops of their stocks… many thought that their money would soon have no value whatever and that it must be exchanged for goods while there was yet time. Others realized that the purchasing mania would help the falling rate of exchange to raise prices, and they therefore bought on speculative grounds…

“German currency is of course stigmatized as shoddy paper of no value. Still, it has always been a striking fact that the German of more modest classes has had sufficient thereof to spend on luxuries such as theaters, skating rinks, cinemas, excursions to the country, and so forth. The amount spent during the craze for buying must have been very large.”

- Mr. Seeds, foreign observer

Debtholders prospered. Stinnes Group, an industrial conglomerate, was able to write off 98% of the debt they had accrued during the gold standard era. This helped the company but caused severe losses among shareholders. Even at the height of the crisis in 1923, the Reichsbank gave credit to commercial enterprises at low rates that was rapidly written off because the real value of the payments was smaller than the initial loan. There were instances where farmers paid off their entire mortgage with the proceeds from selling one bag of potatoes.

From the outside looking in, many foreigners in 1922 thought that Germany was prospering and that the government was lying about its financial difficulties. It’s easy to see why: The upper classes who owned businesses and other real assets could be seen dining in luxurious restaurants and buying high-end goods, which they were incentivized to do by the decline in value of the mark, which meant that any cash they held would lose value in real time.

Things were much different for the poorest classes. According to a study in Frankfurt in 1922, the physical and mental development of children was delayed by two years. Milk was only made available for sick people in winter, and the price of bread and others staples was rising fast. Mothers began searching the garbage cans in rich neighborhoods for scraps of food.

“Our first purchase was from a fruit stand. We picked out five very good looking apples and gave the old woman a 50-mark note. A very nice, white-bearded gentleman saw us buy the apples and raised his hat.

‘Pardon me, sir’, he said rather timidly in German, ‘how much were the apples?’

I counted the change and told him 12 marks.

He smiled and shook his head. ‘I can’t pay it. It is too much.’

He went up the street walking very much as white-bearded old gentlemen of the old regime walk in all countries, but he had looked very longingly at the apples. I wish I had offered him some. Twelve marks, on that day, amounted to little more than 2 cents.”

- Ernest Hemingway

While the rent restriction acts resulted in a shortage of over a million homes, German companies embarked on huge commercial building projects. Any cash that they had on hand was immediately converted into real assets that would retain their value. Business taxes also no longer became an issue. Any income received would be worth far less when taxes were due a year later, and incomes would have increased substantially in that time. The name of the game became trying to delay payment as long as possible.

Things get wild

1923 was the year when things really deteriorated. Between June and July of that year, the mark declined from 600,000 all the way down to 800,000 to the pound. The 1,000 mark note - previously the highest denomination available - was withdrawn from circulation because it was worth so little. New denominations were printed, with the highest having a face value of 50 million marks.

Workers demanded not only higher wages but also daily payment so that they would lose as little purchasing power as possible. Strikes, protests, and other demonstrations occurred throughout the country. Over a thousand people were arrested over the course of two days in after communists rioted in Breslau on July 20th and 21st. Similar protests and riots from different political factions began spreading like wildfire. In August, strikers killed police during a wage riot.

People who held assets faired much better. The stock market tripled between December 1922 and July 1923. This led to an increase in the gap between the haves and the have-nots, which contributed to the demoralization of German society. Business leaders continued to prosper. The owner of Stinnes Group bought up as many shipbuilding yards and paper mills as he could get his hands on, which was duplicated by other investors.

By October 10, 1923 the mark had declined to an official rate of 7 billion and a free market rate of 18 billion to the pound. On October 15th, the official rate was 18.5 billion with a free market rate of 40 billion. Poverty, hunger, and cold swept through the country. Now even the blue collar classes were suffering the same as the middle classes as it was impossible for their wages to keep up, no matter how much they protested.

“Few families can afford meat more than once per week, eggs are unprocurable, milk terribly scarce and bread already sixteen times the price of a few days ago when the maximum price was abolished. It is no doubt true that the expensive restaurants are full of well-dressed people drinking wine and eating the very best in Munich - but they are either German-Americans mistaken for locals, or Rhine industrialists. No one expects political disturbances, but hunger riots are another matter… and the cold. No one can afford central heating.”

- Robert Clive, British Consul-General at Munich

A worker who received 450 million marks per day on October 1st received 6,500 million on October 21st, which somehow managed to give him lower purchasing power than he had on the first of the month.

The situation was deteriorating and people were beginning to starve to death.

The first one billion, five billion, and ten billion notes were printed on November 1st. The sums are staggering. A new mental disorder known as ‘zero stroke’ was diagnosed by German doctors. Patients suffering from this disorder had the extreme desire to continue writing row after row of zeros, due to the requirement of having to calculate every transaction in millions and billions.

“I was sickened by the sights I saw. I happened to pass through between the Friedrichstrasse and Unter den Linden, and in that small space saw three moribund women. They were in the last stages of either decline or starvation, and I have no doubt it was the latter. When I gave them a bunch of worthless German notes, it shocked me to see the eager way they seized upon them - like a ravenous dog at a bone.

“I cannot help doubting whether persons who have not seen these miserable things really realize what they are… Of course we see motor cars and crowds of well-to-do people in profusion in Berlin, but do we really know what is going on in the poorer quarters?”

- J.C. Vaughn, British businessman

The starvation was caused because farmers refused to release food in exchange for worthless marks. There was no absolute shortage of food. Instead, farmers bartered their crops for luxury goods or sold them for foreign currency.

Why you need WiFi money

“Prosperity, as elsewhere, was confined to those in a position to benefit from the production of saleable goods.” - Adam Fergusson, When Money Dies

Many of the early warning signs of hyperinflation that were present in Germany during the early 1920’s are with us now in 2022.

Speculation - Germans speculated in shares of industrial companies, modern people are speculating in puppy coins and WallStreetBets stonks.

Political extremism - People went nuts then, and they’re going nuts now.

Extreme money printing due to an “emergency” - Germany printed due to World War I, America printed because of COVID.

Increased gap between rich and poor - Self-explanatory.

National deficit - Germany’s was caused by reparations payments, ours by spending on nonsense.

Riots and protests - Political protests, workers going on strike, and food riots all played a role in the Weimar Republic. In America we haven’t seen food riots yet but political protests and riots are common, and labor movements are growing in power.

Destruction of the middle class - The middle class in Germany was squeezed from both the bottom and the top. Laborers who were part of a union faired better than the professional class, since they were better able to collectively bargain for wage increases. The upper class prospered due to holding assets.

Blaming inflation on a war - Many tried to blame WWI for the inflation in Germany. Some are attempting to blame Putin for inflation now.

The reason I wrote this article is because I want you all to understand what I’m trying to do with this Substack. I’m giving you advice on how to grow an online business because owning assets is the best way to survive what’s coming. An asset that you 100% control is always better than something you don’t have any influence over.

Throughout the chaos of hyperinflation, people continued to buy products. They bought more than they normally would, not less. This is because any random item they bought - even if it was something they didn’t need - would hold it’s value better than the currency and could be bartered.

People will scramble to keep buying products from your affiliate site or online store. Yes, it’s going to suck (especially from an accounting perspective) and there will be lots of turmoil.

But you won’t starve.

Free articles on Second Income SEO are supported by:

►Surfer SEO - Generate an entire content strategy with a few clicks. This tool features a content editor that is equipped with Natural Language Processing technology that gives you the exact phrases you should use to help your article climb to page one in the SERPs and outrank your competition. If you’re not using this tool, you’re falling behind.

►Jasper - Use an AI assistant to write your content faster and easier. Jasper creates original content for meta descriptions, emails, subheadings, post headlines, website copy, and more.

►Kinsta - Set up your first website with a few clicks. Follow an easy and intuitive process to set up a domain name and hosting. This is step one to earning WiFi money.

What's crazy right now is that the dollar keeps getting stronger *relative* to the other currencies! So the dollar is collapsing, but the other currencies are collapsing faster. Honestly mind blowing to think about. The USD may be the last one standing...and it's still in really bad shape.

You're going to see continual defaults in developing countries (like we're already seeing in Sri Lanka and Lebanon). Anyone with USD debt outside the US is going to get hammered.

Great summary of Weimar Tetra!